Hypermobility and Your Tummy {1, 5}

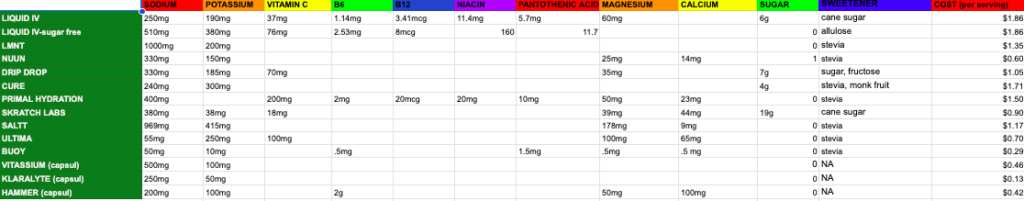

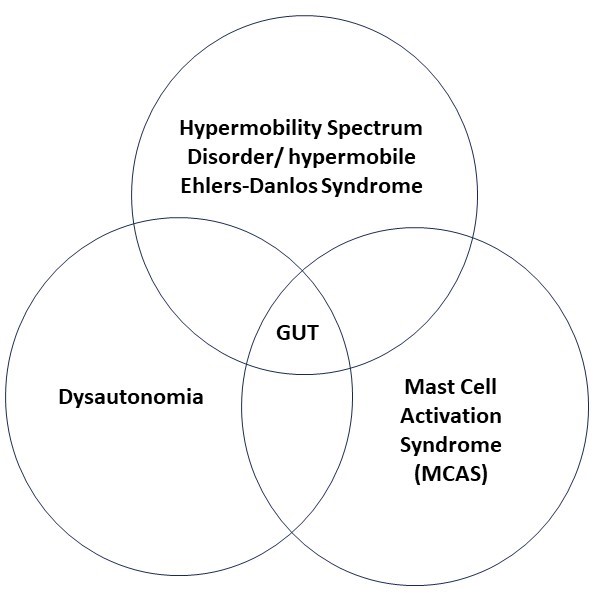

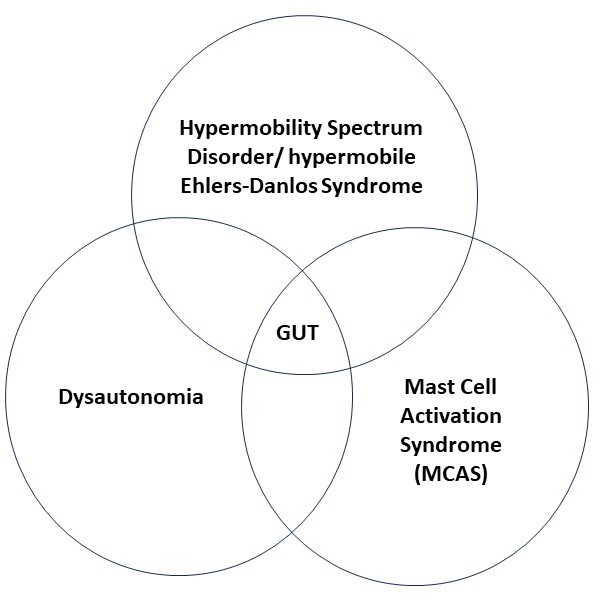

We have been talking about the effects of hypermobility spectrum disorder (HSD) and hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS) on digestion and the tummy in general. In the first blog post on this topic, we looked at the kinds of problems caused not only by hypermobility but also by the frequently associated conditions of dysautonomia (including the condition called POTS) and mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS).

HSD/hEDS can lead to structural problems in the gut. Dysautonomia can lead to imbalance of the nervous system control of gut movements. MCAS creates inflammatory problems. Because the systems of the body are so interdependent, classifying gut problems as structural, nervous system or inflammatory is not in many cases an adequate model. So, the problems that arise in the overlap of function between these different systems are described as “functional diseases”. This chart give a visual representation.

Functional gastrointestinal diseases often do not fit precisely into the diagnostic criteria for specific conditions and are often chronic and painful as well. One gastroenterology clinic reports that up to 40% of their patients present with functional GI diseases. {5, pg. 124}

In this post, we will look at some general principles involved with treating gut problems which are common among people with HSD or hEDS. This is a big and complex area and involves topics not normally at the center of your author’s profession (physical therapy), so our discussion will be somewhat superficial. That is as it should be since we believe. Our goal is to give you a general model of gut problems found in HSD/hEDS. If you are having serious gut problems, you will need the specific and individual guidance of a physician regarding specific medications, diet and therapies. The guidance of your primary care physician, your gastroenterologist and/ or your naturopathic physician will be invaluable.

Please note, if you are looking for a discussion of diets, we will approach this in the third and final post of this series.

Structural Problems {3, 4, 6}

The increased stretchability of the gut wall in HSD/hEDS can decrease peristalsis — the movement of food through the GI tract – leading to constipation. In general, movement which causes contraction of the abdominal muscles can spur peristalsis. For example, walking and also many core strengthening exercises cause “massaging” of the abdominal organs. Direct, gentle massage to the abdomen by a specially trained physical therapist or massage therapist may also be helpful.

Ptosis, or a drop in position, of an internal organ can sometimes also be helped by a physical therapist or massage therapist with special training in visceral manipulation, a form of very gentle manual therapy.

More severe issues such as hemorrhages, bowel perforations and hernias are all structural problems of the gut that very much need evaluation by a physician. As a rule, any new strong pain in the abdomen or new bulge in the abdominal wall should be evaluated by a physician. Bowel movements with black or tarry stool also should be brought to the attention of a physician. In rare cases, there is a problem called an intussusception in which the bowel folds back in on itself. This causes strong pain. While it can often be managed non-surgically, especially in children, it is a medical emergency and needs to be evaluated by a physician.

In our last post, we mentioned “leaky gut syndrome” which certainly sounds structural and is. In leaky gut syndrome, the normally tight interconnections between cells of the gut become loose allowing food particles and bacteria to penetrate deep into the gut wall and at times enter the blood stream. This can lead to whole body immune reactions as the body fights to remove foreign particles and bacteria. While there is controversy among medical doctors regarding this condition, the gastroenterology literature lists it as an inflammatory condition. The inflammatory problems need to be addressed first. Management by a gastroenterologist and/ or a naturopathic physician can be immensely helpful.

Inflammatory Problems {14, 16, 17, 18, 19}

As mentioned in our last post, there are three main inflammatory diagnoses which are more common in the HSD.hEDS population: irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Of these three diagnoses, IBS is more generic. Although, there are several different types including IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D) predominant, IBS-constipation (IBS-C) predominant, IBS-mixed (IBS-M) in which alternating diarrhea and constipation may occur, and IBS-unspecified (IBS-U).

IBS

A number of factors may be underlying these IBS types including bad digestion, infections, food sensitivities or allergies, and stress or anxiety.

Some people with IBS have been found to be low in their production of bile acids which are created in the liver and assist digestion – here supplements may be helpful.

Another problem can be imbalanced bacteria in the gut called dysbiosis, or small intestine bacterial overgrowth of fungal overgrowth (SIBO or SIFO) . Treatment approaches here consist largely of antibiotics, probiotics and sometimes a strict diet aimed at starving the bacterial overgrowth by consuming only foods absorbed higher in the gut than where the overgrowth occurs.

In some, foreign bacteria or even protozoa have taken up residence in the gut. Treatment with antibiotics is the norm in these cases. A proportion of people with IBS report that it came after an infection. This creates yet another type of IBS, post infection IBS (IBS PI).

Sensitivity or allergies to food have led to some dietary approaches which will be looked at later.

Finally, anxiety or stress can be a big factor in IBS, and here too we will talk more about the nervous system below.

Ulcerative Colitis

As the name ulcerative colitis suggests, it is primarily limited to the colon and the rectum. Bleeding from the rectum and bowel movement urgency are common complaints. Here again, a mix of genetic, immune system and environmental factors are thought to be involved. Ulcerative colitis is associated with the western diet, urban living, pollution, and antibiotic use. Oddly, smoking appears to provide some protection.

The primary mainstream medical approach to managing ulcerative colitis is medication based. There are a number of medications available. Steroids are used for more severe cases. We will look into some current thinking on diet in post three. A precaution that is recommended for ulcerative colitis is regular colonoscopies for early detection of more serious disease such as colon cancer.

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease is a relapsing, remitting problem (comes and goes) but also progressive and frequently leads to bowel damage and disability. About half of people with Crohn’s develop complications that require surgery. As with ulcerative colitis, there are a number of different medication options available depending on the severity of the case. Steroids are often used for moderate to severe cases. As with ulcerative colitis, patients are monitored for any signs of more severe pathologies which can develop.

Nervous System Problems {5, 8, 9, 10, 20 }

Gastroparesis

An overactive “fight or flight” nervous system, sympathetic system, can lead to slowing of the movement of food through the gut. This can be part of dysautonomia in people with HSD or hEDS, or can result from a history of severe illness, injury or life traumas. This slowing or even stoppage leads to constipation, often chronic constipation. There is literature to indicate that stimulation of the “rest and digest” nervous system, the parasympathetic system, through the Vagus nerve can be helpful. We will discuss this below.

One of the causes of gastroparesis among people with chronic pain can be the use of opioid medications. If one is using opioid medications for pain relief, it is important to discuss the potential side effects with the prescribing physician or with the pharmacist. Medications to prevent constipation may be prescribed or the opioid prescription may be changed or modified.

Visceral Nerve Hypersensitivity

There is an emerging body of literature which supports a theory that in many painful, chronic gut problems a big part of the problem is overly sensitive gut nerves. This is also an emerging and valuable theory in general chronic pain management for the rest of the body as well. In gastrointestinal literature, this is called visceral pain hypersensitivity (VPH). Neurophysiologists have called the wider theory for other areas of the body central sensitization.

The nerves are the communication pathways of the body. Nerves can become overly sensitive in the aftermath of injury or illness. This can occur at three levels: at the end of the nerve, at the spinal cord, and/ or in the brain.

Pain is not as simple as a stimulus of some kind sending a signal to the brain like a finger pushing a doorbell button. The nervous system is a learning organ and can get too efficient with pain signaling at different levels. In the gut nerves, there are electric particles (ions) which travel through cell wall channels causing the pain signal to start up the nerve. These channels can get stuck open or become too passable making the signal too quick to start. At the spinal cord, there are gate keeper cells that decide which signals make it all the way to the brain, and these can get stuck open.

Finally, the brain can become too efficient at creating the perception of pain. Until they hit the brain though, the nerve signals coming from the body are just signals. The brain has to interpret them. Pain is the brain’s estimate that the body is being harmed or threatened and it does not always get it right. When they hit the brain, the pain signals spread out into a number of brain areas. So, the interpretation of the signals is heavily affected by the experiences already stored in the brain.

If there has been a lot of pain already, the chemical receptors for pleasure which balance the pain impulses in more healthy situations can be depleted. Past history of trauma especially physical and/ or sexual trauma and especially in childhood, can magnify the brain’s sensitivity to pain signals. Similarly, anxiety, depression, confusing medical explanations, high emotional stress levels, and other illnesses creating stress affect the brain’s sensitivity.

Therapies for visceral pain hypersensitivity have been slow in coming. At a basic level, anything that makes the person healthier is likely to help. Knowledge is power, and the knowledge alone that the problem is mostly in the nervous system and not an undiagnosed life-threatening illness can be helpful. Any psychological support including treatment of depression can help. Good and enough sleep are foundational to caring for VPH. Movement in the form of light exercise can be helpful.

Overall, there are several strategies for managing visceral hypersensitivity with medications. One approach is to give medications which target serotonin receptors in the gut. Similarly, there are several other nerve receptors in the gut that are the subject of study to find medications that help to block the pain nerves.

There is a close relationship between the mast cells which we have talked about in other posts and the gut. There is some indication that in a few cases mast cell stabilizing medication can help VPH. {5, 127}. Medications which block histamine receptors, and also, medications which stabilize mast cells have been used for visceral hypersensitivity.

Finally, there is indication here too that stimulation of the nervous system’s “rest and digest system”, the parasympathetic nervous system, through the Vagus nerve, can be helpful with VPH.

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Most of the conditions which affect the gut, even if classified as inflammatory, have a nervous system component usually in the form of increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system. In the involuntary (autonomic or automatic) nervous system, the parasympathetic nervous system works in opposition to the sympathetic. The parasympathetic system is often called the “rest and digest” system and stimulating it by stimulating the biggest nerve of the system, the Vagus nerve, can help calm the whole nervous system. There can be many results from this: decreased gut pain and cramping and bloating, decreased anxiety, improved sleep, improved body temperature regulation, and more.

The Vagus nerve starts at the base of the brain and travels through the neck, into the chest, through the breathing diaphragm and into the abdomen. Along the way, it connects by branches to every major organ system including the heart, glands and gut. More than thirty years ago, experimentation started with surgically implanting wires in the neck to electrically stimulate the Vagus nerve. This form of treatment was so successful for severe anxiety and depression and for epilepsy that it earned FDA approval. In Australia it is approved for migraine treatment. However, it had/ has the problem of requiring surgery.

Over the last 20 years, anatomists have found that there is an isolated area of the ear which can be stimulated using a common, inexpensive, comfortable electrical stimulation device called a TENS (or TNS = transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulator). A growing body of research is showing that this can be helpful for many kinds of problems in which better health will result from calming or soothing the nervous system. This includes IBS, gastroparesis (constipation) and dysautonomia symptoms.

TENS Vagus nerve stimulation, often abbreviated as tVNS, is slowly becoming more known by physical therapists in the US. Here at Good Health Physical Therapy and Wellness we have a simple protocol which we teach which has been useful to many.

In the third and final post in this series, we will briefly consider current thinking on diets for the conditions affecting many people with HSD/hEDS.

Until then, cheers!

Zeborah Dazzle, PT, WWF

Mark Melecki, PT, DPT, OCS

References:

- Wong, S., et. al, The Gastrointestinal Effects Amongst Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Mast Cell Activation Syndrome and Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. AIMS Allergy and Immunology, 6(2): 19-24, DOI: 10.3934/Allergy.2022004

- Beckers, A.B., et. al., Gastrointestinal Disorders in Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/ Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility Type: A Review for the Gastroenterologist. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2017; 29:e13013: 1-10; doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13013

- Castori, M., et. al., Gastrointestinal and Nutritional Issues in Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/ Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Hypermobility Type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 169C: 54-75 (2015); doi 10.1002/ajmg.c.31431.

- Thwaites, P, et. al., Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome and Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract: What the Gastroenterologist Needs to Know. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 37 (2022) 1693-1709; doi:10.1111/jgh.15927

- Farmer, A.D. & Aziz, Q., Visceral Pain Hypersensitivity in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. British Medical bulletin 2009; 91: 123-136; doi:10.1093/bmb/ldp026.

- Camilleri, M., The Leaky Gut: Mechanisms, Measurement and Clinical Implications in Humans. Gut 2019 August; 68(8): 1516-1526. Doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427

- Freiling, T., et. al., Evidence for Mast Cell Activation in Patients with Therapy Resistant Irritable Bowel Disease. Z. Gastroenterol 2011; 49:191-194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1245707.

- Gottfried-Blackmore, A., et. al., Open Label Pilot Study: Non-Invasive Vagal Nerve Stimulation Improves Symptoms and Gastric Emptying in Patients with Idiopathic Gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020 April; 32(4): e13769.doi:10.1111/nmo.13769

- Frokjaer, J.B., et. al., Modulation of Vagal Tone enhances Gastroduodenal Motility and Reduces Somatic Pain Sensitivity. Neurogastroenterol Motil (2016) 28, 592-598; doi:10.1111/nmo.12760

- Cirillo, G., et. al., Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A Personalized Therapeutic Approach for Crohn’s and Other Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cells 2022, 11, 4103; https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11244103

- Kohn, a., Chang, C., The Relationship Between Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology (2020) 58: 273-297; https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-019-08755-8.

- Uy, P., et. al, SIBO and SIFO Prevalence in Patients with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Based on duodenal Aspirates/ Culture. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 116, PS218-S219, October 2021; doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000774444.60980.27

- Danese, C., et. al., Screening for Celiac Disease in Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/ Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility Type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 9999:1-3.

- Torres, J., et. al., Crohn’s Disease. Lancet 2017; 389: 1741-1755; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1.

- Alomari, M., et. al., Prevalence and Predictors of Gastrointestinal Dysmotility in Patients with Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: A Tertiary Care Center Experience. Cureus, 2020, 12(4): e7881; doi.10.7794/cureus.7881

- Asamoah, V., https://www.ifm.org/news-insights/identifying-ibs-root-causes/?utm_campaign=gi&utm_content=263702330&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin&hss_channel=lcp-3054131

- Rao,SSC, et. al., Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Management. Clinical and Translational Gastroenterology 2019; 10:e00078. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000078

- Porter, R., et. al., Ulcerative colitis: Recent Advances in the Understanding of Disease Pathogenesis. F1000Research 2020, 9(f1000 Faculty Rev): 294: 27 April 2020.

- Kucharzik, T., et. al., Ulcerative Colitis – Diagnostic and Therapeutic Algortihms, Deutches Aertzeblatt International 2020; 117: 564-574

- Farzaei, M, et. al., The Role of Visceral Hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Pharmacological Targets and Novel Treatments. J Gastroenterol Motil, 22(4), October 2016, 558-574; http://dx.doi.org/10.5026/jnm16001.