Website: tamingthezebra.org

Mailing List: https://www.tamingthezebra.org/join-the-email-list

Excerpt from: Taming the Zebra – It’s Much More than Hypermobility: The Definitive Physical Therapy Guide to Managing HSD/EDS, Volume 1 Systemic Issues and General Approach

(Due out Winter of 2023)

CHAPTER 5

HSD/EDS and the Skin: Presentation and Management Strategies in Rehab Settings

As with all EDS presentations, skin involvement varies from person to person and may change in severity throughout one’s life. For this reason, the patient and practitioner need to consider some factors when approaching rehab strategies to avoid exacerbating existing issues. Not all patients with HSD/EDS will present with the issues depicted in this chapter. If a patient or practitioner feels that one of the issues may be present, this is an area to explore individually with appropriate members of the medical team.

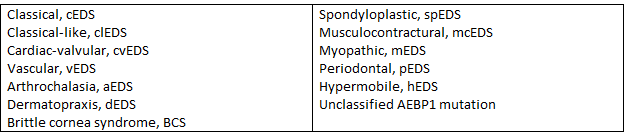

Different classifications of EDS and HSD may have different qualities of skin presentation. Skin hyperextensibility is seen across many different classifications of EDS and more often include cEDS, clEDS, cvEDS, aEDS, dEDS, kEDS, spEDS, mcEDS, pEDS, AEBP1 variant, hEDS, and HSD. Skin fragility (skin that is more easy to tear) is more commonly seen with cEDS, cvEDS, aEDS, dEDS, kEDS-PLOD1, mcEDS, pEDS, AEBP1 variant, and hEDS. Poor wound healing is seen in a variety of severity, more commonly with kEDS-PLOD1, pEDS, AEBP1 variant, and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). Easy bruising is more commonly seen with cEDS, clEDS, cvEDS, vEDS, aEDS, dEDS, kEDS, pEDS, and sometimes with hEDS. Easy bruising that is cyclical (comes and goes) may be more related to systemic flare-ups, such as MCAS reactions.

This chapter presents the different types of skin involvement that might be seen in the clinic and if that issue is present, how to modify treatment or interventions as needed for better outcomes. The individual presentation should always be considered with modifications implemented as needed for the best outcomes in therapy.

Unusual Skin Presentations

There are certain skin presentations in HSD/EDS that do not have a major impact on rehabilitation outcomes. For example, the presence of soft, velvety, doughy skin texture does not usually impact therapeutic outcomes but may change manual therapy approaches. Other similar skin presentations are detailed in Figure 5.1.

| Skin Presentation | Description | Typical Location |

| Molluscoid Pseudotumors | Areas of fat tissue herniating through atrophic scars | High pressure areas, such as the back of the elbows and front of the knees |

| Subcutaneous Spheroids | Areas of fat that have lost their blood supply and become firm areas of calcification, moveable under the skin | Legs and arms |

| Piezogenic Papules | Soft, fleshy nodules caused by fat herniating through the dermis (skin layers) | Heels and wrists |

| Hemosiderotic Plaques | Discolorations of the skin generally found in areas of atrophic scarring | Shins of those with Classical and Periodontal EDS |

Figure 5.1 Common skin presentations, description, and typical location.

While these skin issues more typically present in HSD/EDS are not necessarily something to treat in the rehab setting, it is important for the therapist to note the level of skin involvement and adjust treatment methods as needed to protect the skin from trauma and tearing, and to avoid tissue scraping over these spots as it will inflame, not improve these lumps and bumps. Many will not be able to tolerate tape without a protective barrier applied first.